-

情念と物語の形・デジタル・素 炭 円環に帰す

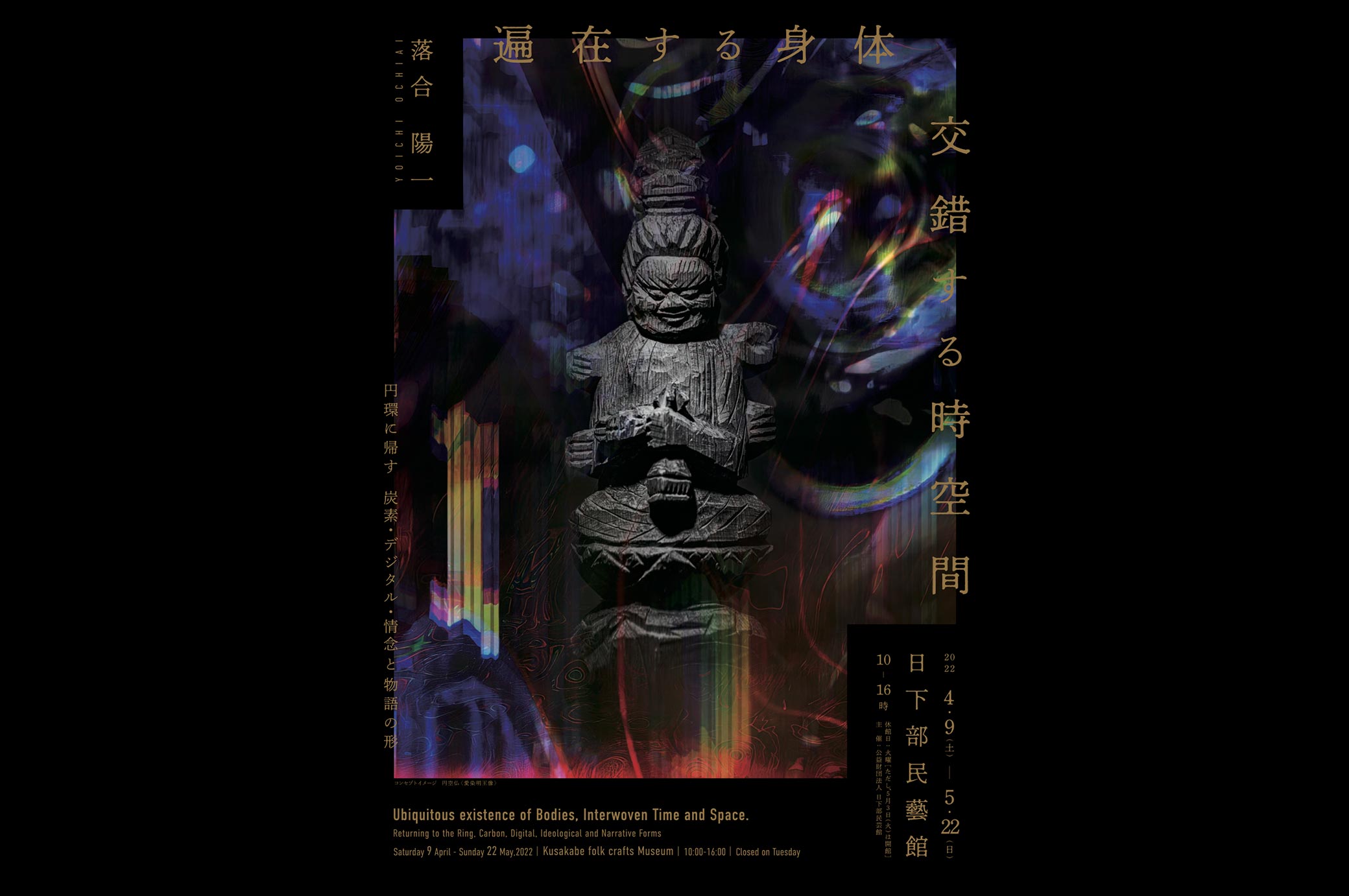

Yoichi OCHIAI Ubiquitous Existence of Bodies, Interwoven Time and Space

- Returning to the Ring, Carbon, Digital, Ideological and Narrative Forms -

ポストコロナの生活に身体が馴染み始めたからか、たとえコロナ禍が過ぎ去ったとしても当面変わらないであろう習慣の中に生きるようになった。レンズとセンサーを通じて変換されたデジタルの身体は瞬時に世界中のあらゆるところへ繋がり世界中を日々旅している。

映像を通じて存在する身体を、今まで以上に意識するようになった。逆に言えば映像や撮像というプロセスそのものは意識の中から存在しなくなっている。時間と空間、身体と情念をデジタルに変換しなければ、存在しえない状態に、世界全体が不可逆の変化を起こし、その中に我々は足を踏み入れている。こうした変化を1980 年、ナムジュンパイクは定在する遊牧民と呼んだ。石油枯渇に対するデジタルのアプローチを彼は語ったが、奇しくもパンデミックと脱炭素の風潮は、ナムジュンパイクの想像とはまた違った形で、我々の存在を定在遊牧民へと変化させてしまった。この定在遊牧性の中に生きる日々の中で、変化した身体性が生活習慣への興味を呼び起こしていることに気がついた。

落合陽一はアーティストとして、境界領域における物化や変換、質量への憧憬をモチーフにデジタル・フィジカル問わずアート作品を展開している。それは元来の質量ある世界とデジタル技術による質量のないデータの世界を親和させることで、風景を調和させるインスタレーションの制作や作家個人のライフスタイルの探求でもある。その中でコロナ禍以前から民藝性に着目している。それはデジタルの自然がなしえたならば、新しい自然の上に民藝は成立するか、という問いでもあった。そして、その民藝への自分の回帰的な期待は、炭素循環・デジタルと分断、生活と規範、さまざまな意味で高まっている。我々が農耕・工業化の末に定住する農耕民や定在する工業民であったならば、定在する遊牧民のような我々の暮らしはどのような民藝を産むだろうかという疑問が創作に自らを向かわせている。

定在する遊牧民を考えたとき、それが仮に狩猟採集社会や農耕社会・工業社会といった社会像を変化させるレベルのインパクトを持つ変化なのだとしたら、単なるメディアとの関わりや技術的発展、解像度の問題以上に、より長期のライフスタイルだったり文明の変遷への思考だったりするものから捉え直さなくてはならないのではないか、と考えた。カーボンニュートラルについて考え

る中で、木に囲まれた暮らしをしてきた飛騨高山の民が、どういった文化を育み、その生態系を維持してきたのか、そこに生じた民藝や伝承とは何か、という視座に立った。

実地で紙漉きを訪問し、木のトランスフォームされた姿である和紙にプリントするワークショップをしたり、各地の文化に触れることで、脱炭素によって分散化・過疎化した定在遊牧性とデジタルの間で、祝祭や共悦の体験を取り戻していくにはどうしたらしいだろうかと考え、偶発性や手業とデジタルの可塑性・一回性の間に答えを得た。また、縄文時代に奇しくも遍在する定在狩猟採集民と化した飛騨の縄文人が残した多くの石棒や土器を眺めるにつれて、身体性と道具の関係性をより深く考えるに至った。木彫の文化を探し求める中で、谷口与鹿によって江戸時代に恵比寿体に彫られた手長足長の姿に、縄文的身体性の極地を見たり、身体性への願望を感じたりした。そういった木と縄文、農耕以前の文化・精神性を読み解きながら、デジタル以後の定在する遊牧性の鍵となる気づきや美学をつかむきっかけを探し求めるようになった。

手長足長は、中国の古典の中で登場する魚を取って暮らす民である。手が長い人々と足が長い人々が協力して魚を取る。その姿は日本に伝来し、巨人の妖怪や、蛸をとる妖怪など多様な形に姿を変え、伝承として保存されている。八岐大蛇に捧げられる稲田姫の両親はテナヅチ、アシナヅチであるし、手長神社と足長神社が長野にあるのも、そういった狩猟採集と木の文化の結節点の一つなのかもしれない。御柱も、石坊も、飛騨高山の一刀彫も、縄文土器も、その生態系や文化は連綿と受け継がれているものなのだろう。

ここで、定在遊牧時代を再考するにあたり、この身体性とライフスタイルへの適応をどう表現していくか考えた。定在遊牧性がもたらしたものは、デジタル化と脱身体化(もしくは身体化)によってもたらされた遍在する身体と交錯する時空間への変貌であると考えている。我々はその身体性をより強く意識するようになると同時に、その身体はバラバラの形に変貌しこの世界中にあまねく存在するようになった。時間は巻き戻り、円環をなし、未来と過去は並列に存在し、身体は複製され、時の流れは意味を持たないものに近づいている。

この時代のデジタルの自然がみせる、情念と物語の形は、民藝とどういう対話を見せ、新しい生活の中での身体性を惹起するのか。デジタルによって交錯する時空間と遍在する身体性をテーマに、変わり移ろいゆく風景を描きたい。

Perhaps it’s because people have become accustomed to a post-corona life, they live with habits that seem to be unchanged for the foreseeable future, even once the coronavirus pandemic has passed. The digital body, transformed through lenses and sensors, is instantaneously connected to anywhere in the world and travels the globe each and every day. Ochiai has become more aware than ever of the body that exists through the medium of images. In other words, the images and the process of imaging themselves have disappeared from people’s consciousness. The whole world has undergone an irreversible change and is stepping into a state in which time and space, body and

emotion, cannot exist without digital transformations. In 1980, Nam June Paik called these changes “stationar y nomads.” He mentioned a digital approach to oil depletion, although, oddly enough, pandemics and decarbonization have transformed our existence into that of stationary nomads in a different way than Nam June Paik imagined. In the days of stationary nomadism, Ochiai found that the altered physicality aroused an interest in the everyday lifestyle.

As an artist, Ochiai creates both digital and physical artworks, and they have the motif of materialization, transformation, and the aspiration of giving mass to digital ideas in the realm divided by massless data and physical materials. This is an exploration of the artist’s personal lifestyle and the creation of installations that harmonize the landscape by bringing together the original material world and the world of massless data achieved through digital technology. Within this context, Ochiai has long been interested in mingei (folk crafts) prior to the coronavirus pandemic. For him, if digital nature has accomplished the marriage of massless data and physical materials, it was a question of whether or not mingei could be established based on a new nature. And his returning expectations grow for mingei to play a vital role in various fields, such as the solution of the carbon cycle with digital and division, life and standard, and more.

If people were stationary agriculturalists or industrialists after the end of agriculturalization and industrialization, the question of what kind of mingei the stationary nomad-like life would produce drives Ochiai’s creativity. When thinking of the stationary nomad, many would ponder if it is a change with such a strong influence that alters the social image of hunter-gatherer societies, agricultural societies, and industrial societies. If so, there is a need to rethink it in terms of longer lifestyles and consider the transition of civilizations, rather than simply in terms of media relations, technological development, and resolution. In consideration of carbon

neutrality, Ochiai wondered how the people of Hida Takayama, who have lived surrounded by forests, have cultivated their culture and maintained their ecosystem, and what mingei and traditions have arisen from this.

Upon visiting a paper-making studio in Hida and holding a workshop to print on the Japanese washi paper, a transformed form of wood, and experiencing the culture of each community, Ochiai wondered how to reclaim the experience of celebration and co-existence between the dispersed and depopulated stationary nomadism by decarbonization and the digital, and found an answer between contingency and handicrafts, and the plasticity and one-time nature of the digital. In addition, as he looked at the many stone sticks and earthenware vessels left behind by the Jomon-era Hida people, who coincidentally became ubiquitous stationary hunter-gatherers, he began to think more deeply about the relationship between physicality and tools. In his search for the culture of wood carving, he has seen the extremes of Jomon physicality and felt the aspiration for physicality in the arm-long and foot-long figures carved on the Ebisu festival float by Yoroku Taniguchi during the Edo era. Ochiai began to search for an opportunity to grasp the key to post-digital nomadism and its aesthetics by deciphering the culture and spirituality of wood, the Jomon, and the pre-agricultural era.

The Tenaga (Long Arms) and Ashinaga (Long Legs) are people who live and work together by catching fish, as described in Chinese my tholog y. Their appearance has been introduced to Japan, where they have been transformed into various forms, such as giant monsters and octopus-catching monsters, and have been preserved in Japanese folklore. In Japanese mythology, the parents of the Inadahime deity, who is offered to the eight-forked serpent god, Yamata- no-Orochi, are Tenazuchi (arm deity) and Ashinazuchi (leg deity). The existence of the Tenaga Shrine (long-arm shrine) and Ashinaga Shrine (long-leg shrine) in Nagano may express the connection between hunting and gathering, and wood culture in Japan. The ecology and culture of the sacred pillars, stone sticks, Itto-bori carvings of Hida Takayama made with a single knife, and the Jomon pottery must have been continuously passed down from generation to generation.

In reconsidering the current age of stationary nomadism, Ochiai thought about how to express this physicality and adaptation to lifestyle. Stationary nomadism has been brought about by digitalization and dematerialization or embodiment. It is a transformation of time and space into an interweaving of ubiquitous bodies. As people have become more and more aware of their physicality, their bodies have been transformed into disparate forms that are ubiquitous throughout the world. Time rewinds and repeats, the future and the past exist in parallel , the body is replicated, and the pas- sage of time approaches insignificance.

What kind of dialogue do the emotional and narrative forms of the digital nature in the current age have with mingei, and what kind of physicality do they evoke in the new life? Ochiai seeks to depict the changing landscape with the theme of time, space, and omnipresent physicality intersected by the digital.